Azerbaijan’s Eurovision Problem

By Jacqueline Hale

Azerbaijan’s victory in the Eurovision song contest brings welcome attention to this often-ignored Caspian country. But success on the stage in Dusseldorf comes at a time when the government has been clamping down on the right of ordinary people to make their voices heard, both on the streets and online.

Days before Ell and Nikki's aptly named song “Running Scared” won the plaudits of the European judges, the European Parliament condemned a recent crackdown on journalists, lawyers, and human rights activists in the wake of a series of pro-democracy demonstrations in the country’s capital, Baku.

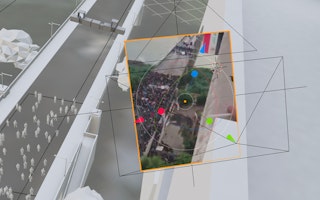

I spent last week with leading independent analysts and activists from Azerbaijan, who told me how between February and April of this year the government has arrested hundreds of people for participating (or intending to participate) in demonstrations; targeted activists on Facebook; and detained, beaten, and even disappeared journalists, lawyers, and bloggers.

Young bloggers such as Jabbar Savalan and Bakhtiyar Hajiyev have been sentenced to two years or more on what Amnesty International has called trumped-up charges. Another blogger, Elnur Majidi, based in Strasbourg, has been accused of plotting the overthrow of the government.

The government clampdown on attempts by citizens to speak out on human rights and democracy persists despite the country’s various international commitments.

Azerbaijan is a member of several organizations promoting European standards, such as the Council of Europe, and has signed commitments to reform under the European Union Neighbourhood Policy—but the level of commitment is superficial at best. As far as proving itself on the European stage, Eurovision is as good as it gets.

Four years on from the joint Neighbourhood Policy agreement with the EU, there has been backsliding on basic standards rather than progress on reform pledges. Parliamentary elections in autumn 2010 were assessed by international observers as flawed, and there has been a de facto ban on opposition gatherings in Baku since 2005.

Despite a promise to cut red tape for registering human rights organizations, the government has increased the administrative burdens and reporting requirements, recently forcing the closure of two organizations, including Human Rights House, which had worked as a hub for young and independently minded activists in the country.

Azerbaijan is the only country to refuse a special rapporteur's visit to its territory (the Council of Europe Special Representative on political prisoners), and a leading journalist, Eynulla Fatullayev, who dared to speak out critically about the authorities and the situation of human rights in the country, remains in jail on trumped up charges.

The Eurovision victory of Gasimov and Jamal is of little consolation for many activists languishing in Azerbaijani jails or threatened abroad. Their catchy love song steers clear of issues sensitive to the government and Eurovision is a different world from the common reality of censure and restrictions inside this country, once the Muslim world’s first democracy.

Nevertheless it can be a point of leverage. Next year Baku will host the song contest—and welcome the international media, much of which remains off the air in Azerbaijan. Before then, the authorities need to prove in practice that they can guarantee freedom of expression and assembly—universal rights underpinning the commitments it has signed up to at the Council of Europe and with the European Union.

The international and European media—essential to the success of the Eurovision contest—should stipulate their attendance on the existence of freedom of expression and a truly independent media in the country and the removal of restrictions to accessing external broadcasters.

The EU should be clearer in its expectations regarding Baku’s reform agenda and the state of democracy in the country. Azerbaijan’s oil and gas stocks will not guarantee a stable energy supply for Europe if the governing institutions restrict the basic rights of its people.

A competition that prides itself in bringing together over 40 competing countries and 120 million viewers should be held in conditions where the voices of ordinary citizens are free to be heard. The EU, European institutions, and international media can help Baku solve its Eurovision paradox before May 2012.

Until October 2013, Jacqueline Hale was responsible for managing work relating to Central Asia and South Caucasus, energy, and human rights issues at the Open Society European Policy Institute.